To GamberoRosso

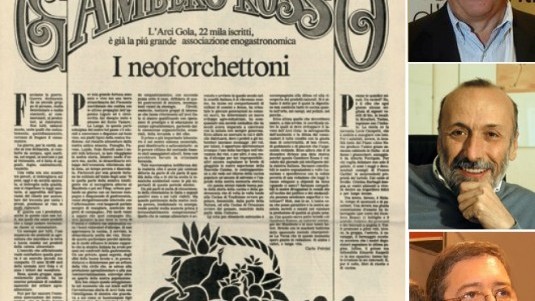

There are some rock groups that maintain their name but change their lineup to replace the original members. Next December 16, Gambero Rosso (Red Shrimp) will celebrate its first 30 years and none of those who were there at the beginning, way back in 1986, are still there. These included Stefano Bonilli, who died two years ago, yours truly and Cristina Barbagli, who at the time was one of the publication’s bulwarks. To mark the upcoming anniversary, allow me to re-print an excerpt from “Memories of a Wine Taster”, a memoir I wrote for Einaudi in 2006 when we were all still at Gambero Rosso. The text even had Bonilli’s approval and so I think it can be considered an authentic account of how things went.

“Between my job as a school teacher, my courses at the Italian Sommeliers Association (AIS), where I had been an instructor since 1980, and the articles I wrote for several magazines, things were going pretty well for me. But my big opportunity had yet to arrive. This had less to do with fame or fortune than a desire to have my say in a sector where I thought, wrongly, I knew everything. Then one day in November 1986 I got a phone call from Stefano Bonilli, an ex-journalist and former rising start at the Il Manifesto, the famous Communist daily. He had recently been forced to leave state broadcaster RAI with the entire staff at “Di Tasca Nostra” (Out of Our Pockets), a TV program dedicated to consumer protection hosted by Tito Cortese. The show was shut down after a suit was filed by a well-known food company that was unhappy with the results of inquiries the program had carried out. Bonilli decided to go back to his first love and proposed to il Manifesto, where he had worked for 15 years, a monthly insert dedicated to consumers. They gave him a green light but made clear it could not cost the newspaper a penny. He got down to work knowing that there was nothing in the world of gastronomy like what he wanted to do. His relations with il Manisfesto had been rocky after an article he wrote in the 1970s about the restaurant of Peppino and Mirella Cantarelli, in Samboseto, near Parma, which was perhaps the first to use exceptional prime ingredients that were prepared in a simple manner and offered with a stellar wine list. He entitled the article “A Conversation with Cantarelli” and it caused quite a stir because some thought he mimicked an interview that Rossana Rossanda, one of the newspaper’s founders and its “maitresse à pensér”, had published entitled “A conversation with Althusser”. His critics felt his article was disrespectful because it put one of the most famous Marxist thinkers on the same level as the culatello di Zibello cold cut. But now he could finally have his revenge and he buckled down to work. For the graphics he contacted Piergiorgio Maoloni, a genius in the sector who unfortunately recently passed away, and put together a small team of collaborators. Among these was Cristina Barbagli, a bio-nutritionist and great expert in comparative tests on food, and Edoardo Raspelli, a spirited Milanese food critic and terror of restauranteurs because of his sometimes scathing reviews.

What was lacking was an expert on wine and it was Raspelli, who I had met a few years before, who suggested to Bonilli to contact me and he did. The publication’s original name was “al (at) Gambero Rosso”, which was chosen for three basic reasons. It was the name of the tavern where Pinocchio was tricked by the Fox and Cat and we wanted our publication to defend consumers or, in other words, all the Pinocchios possible. Secondly, it was a very popular name for restaurants and trattorias in Italy, which would also be reviewed by our publication. And last but not least because the Left in Italy was going backwards in elections just the way a shrimp does and we were being published by il Manifesto.

This is how the Gambero Rosso adventure began and was first hosted on via Tomacelli in Rome, where il Manifesto still has its offices. In the beginning there was only a half a desk available which Bonilli had to share with another journalist and while there was room for a chair and the phone, it was not big enough for a typewriter. The typewriter, in fact, was on another table that did not have a chair and in order to use it we had to stack up phone books to use as a seat. Bonilli had a blue Fiat Uno 45S which he later sold to me to replace my Bordeaux Fiat Panda 30 so I would make a better impression as a wine expert. We had little money but high hopes and dove into our endeavor with passion. I knew il Manifesto only from reading it off and on as a student and would never have imaged that an insert in that newspaper which dealt with food and wine would create such a hornet’s nest. It should be noted that not everyone who read the Communist daily agreed with its politics. In fact, it was read by people of all political persuasions as well as many in the economic and financial sectors who, along with many Leftist readers, were not at all scandalized by what we wrote. What’s more, we also collaborated closely with the recently formed Arcigola, which evolved into Slow Food, and its charismatic founder Carlin Petrini.

Wine has from the beginning always been one of the key arguments of Gambero Rosso and we were the first in Italy to rate wines using the American 1/100 system. Then, in the spring of 1987, during a meeting at Arcigola’s headquarters in Bra, the idea came up to create a guide to Italian wine. Taking part in the meeting were Carlo Petrini and Gigi Piumati for Arcigola and yours truly and Bonilli for Gambero Rosso. At the time, Veronelli’s Bolaffi guide had not been published for a few years and no other guide had taken its place. And so we went ahead with ours. We decided that the wine should be ranked on a scale of 1-100 but this seemed too questionable and difficult. To make things easier, I came up with an idea. A bottle of wine holds an average of six glasses but it is not healthy to drink a whole bottle alone. Thus a bottle is best consumed by two people and, if the wine is very good, they can easily finish it. This means three glasses a head and so the best wines should have a rating of three glasses, those not as good two glasses and those that are at least worth trying should get one, while those that did not convince us would not have any. While it may have seemed a game, this system of evaluation, perhaps due to its immediacy and simplicity, had an enormous success and today the terms ‘three glasses’ or ‘a three-glass wines’ are commonly used among wine lovers both in and outside Italy. Not bad for a school teacher…

At the beginning Italy’s Wines, the guide’s original name, made waves because people at il Manifesto were writing about quality wines. Then, little by little, it gained credibility and popularity and over the next 20 years became a point of reference in the world of Italian wine. Today the guide sells close to 150,000 copies a year between its Italian, German and English editions. The guide is regularly at the top of the best-seller list and is the most read book on Italian wine in the world. Turning it out year after year was no easy task. Wines change and harvests differ and so the guide needed to be totally re-written each year and it takes at least five months to carry out all the tastings necessary to be able to evaluate over 15,000 wines. It is a humongous endeavor made possible by the contribution of over 100 collaborators, coordinated then by yours truly and Gigi Piumati of Slow Food. And thus what was truly revolutionary about this guide was that tasting panels throughout Italy had the honor of making the evaluations and not just a select few critics.

Italiano

Italiano