The origin of Sassicaia as told by its creator

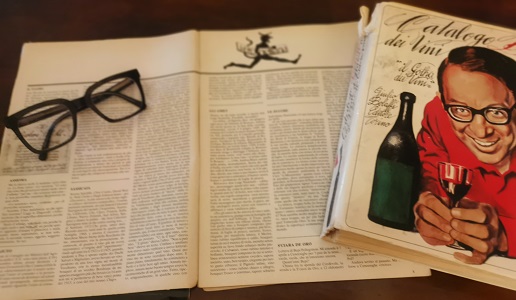

Re-reading a 1979 article by Luigi Veronelli for the magazine Vini&Liguori, which he ran at the time, I came across this lovely story on the birth of Sassicaia told by none other than Marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta.

In an old issue of the magazine Vini&Liquori, from April 1979, Luigi Veronelli, who was its editor at the time, commented on the victory of Sassicaia 1972 in an international contest and published a letter from Mario Incisa della Rocchetta, the father of Nicolò and grandfather of Priscilla, who recalled how that wine came about. For me, it was such an important account that I decided to republish it and offer it to you 43 years after it came out. The “Veronelli-style” is both irresistible and fascinating.

Serena Sutcliffe, Clive Coates, David Wolfe, Nick Clark and Hugh Johnson every year – for the magazine “Decanter” (for us) the most authoritative magazine in its field – examine the most famous Cabernet Sauvignon wines in the world (from Argentina, Australia, California, Chile, Cyprus, France, Italy, Lebanon, New Zealand, South Africa and Spain) and this year gave their The Best Cabernet Sauvignon in the entire world prize to… Sassicaia 1972. What a joy, my friends. I can still remember tasting, many years ago, the first vintage, a 1968, and still have a letter from the Marchese Mario Incisa della Rocchetta with the story (which still moves me being the continuation of what he had already told me about that wine) of the “origin of that experiment”. He wrote “It all began between 1921 and 1925 when, as a student in Pisa and often a guest of the Duchi Salviati family in Migliarino, I tasted a wine produced from their vineyards in the Vecchiano hills. It had the same unmistakable bouquet of an old Bordeaux that I had tasted rather than drank (at 14 was not allowed to drink) in 1915 at the home of my Chigi grandfather”.

Between 1920 and 1930 he was in Piedmont, in Rocchetta, where he tried their Pinot Noir, advanced his studies of French wines and became convinced that while Pinot was fine for northern Italy, central Italy was more suited for Cabernet (also because, he noted, “for the bouquet I was looking for, Cabernet was certainly more suited that Pinot”). “I then moved permanently to Bolgheri in 1942, looking for a best place to carry out my experiment. At the time, wine was made using the traditional Tuscan “Governo” method (ed.note: adding rasinated grapes to the barrels to spark a minor secondary fermentation that raised the alcohol content). I remember how my father, a Piedmont native, would say that in any other part of the world a “governed” wine would not end well. And this was true in any country, with the exception of Jerez, with a wine made using a kind of ‘solera’ method which at best would produce vinegar, certainly not sherry.

Even if Bolgheri wine did not become vinegar it was still always bad, although on the bright side each year it produced a different defect: “this year it came out frizzy”, the vintner would say; or “this year it was maccheroni”. No one knew why there were all these variations. And then the red wines were always a bit “brackish”, due to the vicinity of the sea they would say, which is why most people cultivated white grapes. Based on all this knowledge, I chose for my Cabernet vineyard (a tiny one of 1,000 vines), a plot situated 350m above sea level, to avoid the wine being brackish, with a southeast exposure. This is because I had read that the vineyards of Cote d’Or and Médoc generally had similar exposures. Then, as luck would have it, I was able to obtain from the Salviati estate a certain number of “cuttings” from their Vecchiano vineyard that I was able to graft on to stocks in my plot. The wine was made in a haphazard way, the winery was never clean and the equipment was nonexistent. The “barriques” (since we were dealing with Cabernet) leaked from every slat and the wine was bottled as best we could, which meant we were able to put away some two hectoliters a year. The opinion of farmers and local experts who tasted it in March (which in the area was when a wine was “done” for sale) was unanimous every year: it was crap. “It could catch fire” said one. “It’s turned” said another. “It’s undrinkable” said a third. Confused and humiliated, I did not dare to defend it and literally forgot I had it. Years later, almost by chance years later, I remembered it and cautiously began to drink it and offer it to friends. In good years and less than good years it always had the same characteristics of a great wine. It was made, I repeat, in an artisanal way, sometimes with a volatile acidity that was over the top, with dregs that did not stick to the bottle, as would be acceptable for a “queue de renard”, and broke up and navigated through the wine. The bottles were too dark or too green and were unevenly filled, closed with corks that were 1.5cm long and so on…”

“No doubt (it can happen on first try)” he wrote. “Equally without a doubt, I am proud”.

(Luigi Veronelli)

Italiano

Italiano