Old tales

Are tales just old stories? Perhaps, but what is important is to not forget the recent history of Italian winemaking.

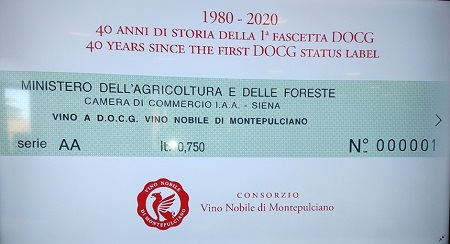

A couples of weeks ago, during the Tuscan Wine Previews, the Consorzio del Vino Nobile di Montepulciano producers’ association asked me and Christian Eder, a talented Austrian journalist, to conduct a tasting of different vintages of Vino Nobile to recount the history of the appellation over the past 40 years, since it received a DOCG classification.

The audience was composed of sector operators, international journalists, producers, enologists and sommeliers. This being the case and out of respect towards them, I thought it best not to limit myself to simple organoleptic explanations, since they were all capable of drawing up their own, and instead decided to talk about the vintages and the stories of people I had the opportunity to meet, some of whom are no longer with us.

A colleague, whose name I will not give because he did not have the courage to tell me it to my face, later said backstage that it was a waste of time to recount all those “old tales”. This because they were old hat and boring. I say no more but here will offer you my justification.

A colleague, whose name I will not give because he did not have the courage to tell me it to my face, later said backstage that it was a waste of time to recount all those “old tales”. This because they were old hat and boring. I say no more but here will offer you my justification.

In many countries, writings about wine have focused making sure that recent history, and even older, is examined in depth and recounted in books that have had an important role in increasing general knowledge of wine. Authors like Hugh Johnson, Jens Priewe, Burton Anderson, Jancis Robinson, David Peppercorn and Sheldon Wasserman, just to name a few, have made important contributions in regard to wines of the past. These were in part Italian but above all French wines and even some German ones along with those from elsewhere in the world.

In Italy, the work done by Luigi Veronelli, who died in 2004, is quickly being forgotten and with it a major part of recent Italian wine history. This to the extent that many young wine lovers do know who were the protagonists of that authentic wine renaissance for Italian wine starting in the second half of the 1960s. They do not know who Giacomo Tachis was nor what Mario Schiopetto meant for Friuli wines, while the story about Franco Biondi’s last Brunello was by far the most read these past months on DoctorWine. I will not go into Violante Sobrero or Giulio Venco because by now very few people have even a vague idea who they were.

This being the case, it is important not to forget history and perhaps the time has come move away from trivial tastings, during which one shows off using abstruse terms and a superficial technical knowledge. And perhaps those “old tales”, boring as they may be, are more new, profound and even interesting than any other approach. This because they allow the new generations, including those abroad, to understand that behind a wine, an appellation, a territory and there were men who spent their lives to create the foundation of what we find today.

Despite all this, there does not exists in Italy a book comparable to what has been published elsewhere and there is a real risk that the memory of an extraordinary era, arguably a pioneering one, will be forgotten. I will not claim that the little I tried to do in Montepulciano was anything more than a small contribution, considering that I am one of the few survivors of those times, but to brand it as “old tales” seems out of place. At the end of the tasting, a South Korean journalist thanked me. And that was rewarding indeed.

Italiano

Italiano