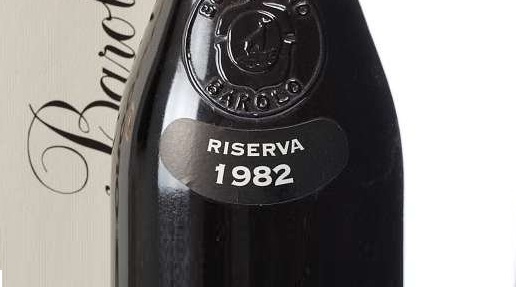

1982: A mixed blessing

The heat and drought of 1982 produced bold reds with softer tannins, making them easier to drink when young and resulting in a change in winemaking.

The summer of 1982 seemed as if it would never end. It was extremely hot in July and August with the temperature often over 40°C in many part of Italy accompanied by drought everywhere. The situation was the same in Bordeaux and other parts of France. The heat caused ripening to be interrupted, somewhat like in 2017 and 2003, but back then such a hot year was unpredictable. Furthermore, this came after two cool and wet years, 1980 and ’81, and others that, with the minor exception of 1978, were not that great, especially 1976 and ’77.

In other words, 1982 caught almost everyone off guard. But this was only one of the factors that made this an authentic watershed year. At the time, in fact, above all in the United States, a new and different trend in wine criticism was evolving that paid more attention to the drinkability and immediacy of wines. Before then the great reds, be they the Grand Cru Classé of Bordeaux, Barolo or Rioja, had the fundamental characteristic of needing to be aged long before being read to drink. The bottles were thus kept for many years in the cellar, sometimes not always adequate, with the consequence that the wines were often too evolved.

Robert Parker, who in those years had founded The Wine Advocate, and Marvin Shanken, who created Wine Spectator, were addressing a new generation of consumers who did not want to run that risk and who, above all, did not want to drink wines that were too edgy because they had not aged sufficiently. All things considered, this responded to the qualities of California wines that were gaining notoriety, as anyone who has seen the film Bottle Shock, which dealt with the 1976 Judgement of Paris wine tasting during which the 1973 Château Montelena Chardonnay “knocked out” all the French wines, knows.

For this reason, a vintage like 1982, with its bold and naturally soft reds, which were a bit more “southern”, seemed tailor-made for the new trend.

In Bordeaux, they took the bait and produced wines that did not age as long but were more comprehensible to a new and, for the most part, younger wine drinking public and, above all, from countries different from Britain where they adored the traditional reds. Some of the wines were even monumental, like Château Latour, although many “purists” turned their noses up to them.

In Italy, above all in Piedmont, vintage 1982 coincided with the debut of the Barolo Boys – Altare, Sandrone and Clerico, in particular – with their wines that were more immediate and which had an almost instant success abroad. It should be noted that at the time Barolo was not at all a “trendy” wine and absolutely did not have the draw it has today. This does not mean that there were not great “traditional” versions that year like those from Bruno Giacosa, Giovanni Conterno or Bartolo Mascarello, only that it was not common to open aged bottles of Barolo or Barbaresco. Towards the end of the 1980s, Carlo Petrini, Stefano Bonilli and I joked about how it was no longer necessary to wait until it was way below freezing and you were roasting venison to open a great Langhe red.

After 1982 there was a new normal and all wines became less edgy, the result of a technical revolution that, even if at times was excessive, was a sign of the times and marked the beginning of a trend that continues today.

Italiano

Italiano