The tree of life

In each of the countries bordering the Mediterranean an ancient wisdom honouring mankind put the culture of the olive tree and its oil at the centre of organized society. To light, feed, anoint and nurture were the essential functions that defined this oil’s essence and promoted its spread “to the very edges of the desert” (Huxley).

The domestication of the olive tree is the most fascinating meeting and greatest technical challenge that man has ever had with a fruit tree. The endeavour to harvest the fruit of the ‘tree of life’, as it has been called, began with the ancient Mesopotamian peoples and on the caravan routes that connected the Mediterranean to the East along the Euphrates.

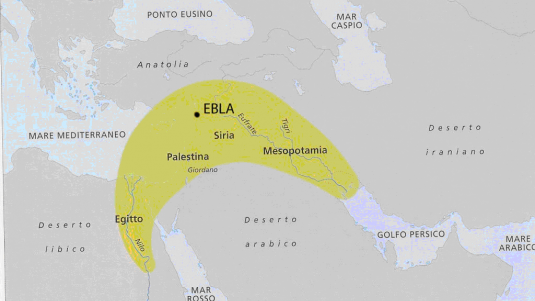

On that strip of land bordering three continents that the Romans called ‘mezzaluna fertile’ (the fertile half-moon), thanks to the work of pioneering farmers “gifted with imagination and the ability to see far” (Arnold Toynbee), cultural forms were born – starting with writing – that have become archetypes of human history. Indeed, writing and agriculture with the same destiny.

In the country in which barley and wheat originated, the economic importance of the olive was already documented in the Royal Library of Ebla (Syria) in the third millennium BC and, as the research currently stands, we can safely assert that Ebla was the first of what we now think of as ‘olive oil cities’.

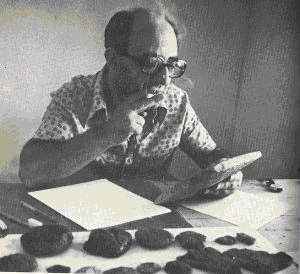

The ambitious Italian archaelogical mission led by Professor Paolo Matthiae led to what was undoubtedly the most important archaelogical discovery of the 20th century. After years of searching at Tell Mardikh in Ebla, it uncovered an entire archive, the largest ever found, that revealed “a third pole of civilisation – along with Egypt and Mesopotamia – whose centre was in Syria, in a place not far from ancient Aleppo”.

This quote is from the great Assyrian scholar, Giovanni Pettinato, who produced the first translation of the archive. He soon unveiled it to the international scientific community, following it up in later years by an enormous body of research and scholarship.

The archive, still currently in Syria, consists of more than 17,000 clay tablets inscribed with cuneiform characters in an original Semitic language (the first ever to be written) called Eblaite that is related to Phoenician and Hebrew. It includes diplomatic letters, literary and scientific texts, economic treatises and bilingual dictionaries, as well as accounts and international contracts, many of which were related to the sale of substantial quantities of olive oil.

The people of Ebla were unrivalled masters of trade and developed a large number of agencies in cities and kingdoms in the ancient Near East, from Palestine to Egypt, Turkey to Iran and in the Persian Gulf where textiles and metal goods, refined jewels and precious manufactured goods were sold. They were even able to guarantee the stability of prices of their silver currency with gold.

The demand for oil there must have been very high. Among the objects found in the royal palace there is an alabaster lamp, a gift from the pharaoh of Chefren (Khafre) whose name is carved into it. Enormous quantities of lamp oil must have been burned in the many work sites used to erect and decorate the interiors of his famous pyramid with figures and hieroglyphics. To meet the demand from such a vast area they had huge plantations and thousands of cysterns. Above all, their oil must have been known for its good quality. Like water.

On one of the tablets there is a fascinating juxtaposition between those two words – water and oil – placed, or rather carved beside each other with beautiful realism in the cuneiform text that warn of steep fines if the products were deemed to be ‘bad’.

So, for the first time in history, the inviolable ‘sacredness’ of these two primary resources for life and for the community is proclaimed, as symbols of mutual cohabitation and respect.

That was at the time of the first urbanisation – known as the great ‘urban revolution’ – that was taking place in Syria and in Iraq by the Sumerians in the third millennium.

“It was a real laboratory where socioeconomic models were successfully being experimented that were to determine historic changes in the history of mankind,” (Pettinato) from which, many centuries later, the Minoan, Greek, Hebrew, Arab, Roman and Etruscan civilizations took inspiration.

There is, however, one aspect to particularly consider that will help us understand how the royal world functioned in Ebla, where the olive was at the centre of a very advanced society that was also open to the world. As we know, the ritual anointing in theocratic societies of that time was reserved for just three categories of people: priests, kings and prophets.

The olive is the heliophilus (or sun-loving) plant par excellence. It is believed that using the oil is like absorbing pure solar energy, soaking in the very essence of the sun’s being and even the organic entirety of the planetary system that includes the earth. It’s thought to generate a ‘cosmic’ awareness in its users, and an assumption of public responsibility to inspire, support and orient life and the fate of humanity. We’ve lost the understanding of these sorts of concepts but they were very common in those times.

This is a ‘complete’ concept of reality, a metaphysical vision of the world that runs through every ancient culture and that still remained at the heart of Humanism at the beginning of the modern scientific revolution.

As Pettinato highlights in his extensive research, “royal power at Ebla was the prerogative of the queen, of the female line: the king became such not from dynastic decendance but by marrying the queen, who was the true and sole holder of the royal lineage”. The texts reveal that the anointing ritual was reserved for the queen: oil was poured onto her head on her wedding day.

The ritual may be religious but the structure of power is essentially ‘secular’, unlike in Mesopotamia and Egypt where the kings were considered incarnations of the divine world.

The ritual may be religious but the structure of power is essentially ‘secular’, unlike in Mesopotamia and Egypt where the kings were considered incarnations of the divine world.

Women in Ebla held positions of importance and prestige. They commanded salaries that were equal or even greater than men’s, had access to the highest positions in the state, and equal status on taxes paid to the treasury.

This is not merely a question of erudition. It’s also a way of interpreting the signs from the distant past. Out of the layers of sand and stones come unexpected flashes of wisdom that help us know ourselves better. They remind us too that it was women who undertook the first forms of agriculture and craftmaking, becoming thus ‘queens’ alongside their men.

Now that farming expertise and oil-extraction techniques permit us to reach levels of quality that were unthinkable a few years ago, the hoped-for economic improvement of the best olive growers is poised for an answer of conscience and culture. It could come from my country – Italy – or perhaps even from the mythical Ebla.

From its position at the heart of the Mediterranean, Italy now has a historic opportunity that’s too important to be missed. We’ve come to appreciate that our exceptional patrimony of olive culture is not just a part of the landscape but also represents the cultural and moral legacy of our ancestors.

By avoiding localistic temptations and without giving in to the fickleness of the oil classifications, Italy can remain loyal to that ‘matrix’, to that point of convergence of the early great civilizations which were home to the first fathers of our West, and begin a compelling and serious work on memory.

The olive isn’t afraid of time. It has millennial longevity. Today it’s our best natural defense against desertification. All it asks is for our presence, consistency and care: that may be why Qohelet associated it with Wisdom.

The time is right for the birth across Europe of a renewed desire for an effective meeting with peoples and cultures that we may have looked down upon in the past but that now, thanks to the olive tree, we understand share our same fate.

(First written for “Olissea”.Translated by Carla Capalbo)

Italiano

Italiano